We’ve talked about f-stops in previous posts, but what the f-stop is an f-stop? FYI, it might get a bit technical. But, you don’t need to know how every single part of a car engine works to drive it. The technical stuff is only for your nerding pleasure.

You get f-stop numbers, like f/1.4 or f/16 by dividing the diameter of the aperture opening in millimeters by the total focal length. For you math majors out there, the secret formula is f number = focal length / diameter of aperture. F-stops are constant, regardless of the brand of lens. F-stops relate to the aperture setting that will produce the depth of field that you are going for.

For example, if the focal length of the lens is 85mm and the diameter of the aperture opening is around 47mm, then use the formula to get the f-stop. We get 85mm focal length / 47mm aperture diameter = f/1.8. Likewise, the f number for a 35mm lens with an aperture opening diameter of 5mm has an f number of f/7.

Now, if you know the f number, but want to find out the diameter of aperture opening, divide the focal length by the f number. For example, to find out the size of the aperture opening in millimeters for a 35mm focal length at f/7, divide 35 by 7. The size of the aperture opening for a 35mm focal length at f/7 is 5mm. The f-stop varies as the size of the aperture opening increases or decreases. Do you need to know this formula? No! But, doesn’t it make it more fun to know? Cue NBC’s “The More You Know” jingle now.

So, the larger the f number, such as f/11 or f/64, the smaller the aperture opening. The smaller the f number, such as f/0.95 or f/1.8, the larger the aperture opening. It sounds almost counter-intuitive, but once you understand it, it’s no problem.

Why is the f-stop called an “f-stop”?

Back in the good ol’ 1800s, to cut the amount of light entering a lens photographers had to add a device onto the lens. These devices were called “stops” because they stopped a certain amount of light from entering. This is like a hat shielding your eyes on a sunny day. If you wanted to cut the light even more, then you had to take that “stop” off and install one with a smaller opening. Pretty soon, photographers were carrying a bunch of stops around with them. “Yeah, I got a stop for that!” So, to make it more convenient, lens manufacturers started building aperture blades into lenses to cut light. Now, we don’t have to carry stops with us! But, the lingo of stopping down a lens to cut light is still used today.

What does the “f” stand for in “f-stop”?

The “f” in “f-stop” numbers, such as f/5.6 or f/8, stands for “focal ratio” or “focal stop.” Because the formula for calculating f-stops use the focal range of the length, the measurements use the prefix “f”.

Then how many dang diddly f-stops are there?

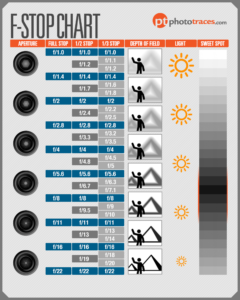

The easiest to work with are full stop increments. Each stop either doubles the amount of light entering the lens or cuts it by half. For example, going from an f-stop of f/1.4 to f/2 means that you are cutting the amount of light by one full stop. Going from f/11 to f/5.6 means that you increased the amount of light intake by 2 full stops (from f/11 to f/8 to f/5.6). There is a pattern. Full stop increments are easier to remember and what photographers have used for over a century! But, there are also fractional increments of f-stops that allow finer adjustments. Examples of fractional stop increments are f/3.5, f/7.1, f/9, etc.

Here are the full stop numbers you should know, along with their general qualities:

Don’t worry too much about the 1/2 and 1/3 fractional stop increments now. Heck, even I don’t use them much, nor know by heart, aside from f/1.8. I still stick to full stop increments whenever I can. I only use fractional stop increments to fine tune the exposure if necessary. But, I recommend learning the full stop increments. It will help you compensate for settings changes faster.

Also, did you notice a pattern with every other f-stop? Notice that going from f/2 to f/4 is closing down the aperture by 2 stops (from f/2 to f/2.8 to f/4). F/4 cuts light from f/2 by four times the amount, or 2 stops. Likewise, opening an aperture from f/5.6 to f/2.8 means that you let in 2 stops of light (from f/5.6 to f/4 to f/2.8). Because of the 2-stop difference, f/2.8 lets in 4 times as much light as f/5.6. Remember, because aperture is the third leg of the exposure triangle, if you change the aperture setting, then you may also need to adjust the others.

So, get out there and start taking photos of your cat, sharks, your offspring, and crazy uncle Ned. Play with exposure settings and see what you come up with. Challenge yourself. Think of tough scenarios, such as only using one focal length or aperture that day. See how you can solve problems that arise from such challenges. The more you prepare yourself for problems that may come up, the quicker you’ll be able to solve them when they arise. Find what appeals to you and how you can recreate it for your own signature style.

Thanks for reading this post, everyone! I hope that it helps you become a better photographer and gives you a greater love for this beautiful art. It’s a joy to share this information with receptive people! If you have tips or tricks, or any questions, then please drop a comment below and share your thoughts. Thanks, again!

Bonus tip: If you can keep your ISO consistent, then all you have to consider are the aperture and shutter speed. If you’re shooting in-studio, then, your ISO, aperture and shutter speed might not change. If you are shooting outdoors, where ambient light is always changing, then try to keep one of the variables constant. For example, keep the aperture the same at f/11, but only adjust the shutter speed and ISO last. This way, you don’t have to worry about too many things at the same time.

Blog question: Let’s see how much you remember. Suppose you want to shoot a portrait. And say, you want the subject in focus, but the background blurred. What are the 2 main settings to consider to achieve this? Leave a comment below! Feel free to ask any questions. Stay tuned for next week’s blog post!